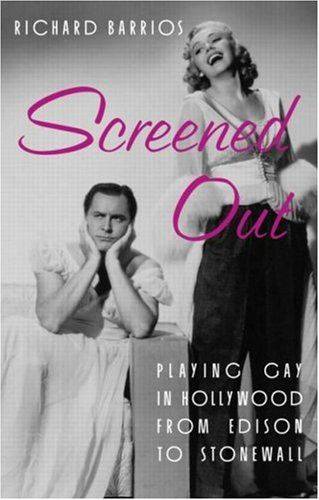

Screened Out

Playing Gay in Hollywood from Edison to Stonewall

Richard Barrios

The book features homosexual images from a variety of movies, from shorts to documentaries, from the horror genre to musical fantasies. Some of the earliest images appeared in comic westerns, such as Algie, the Miner in 1912, where homosexuals contrasted with more virile men. Many of the early images indicated homosexuality through cross-dressing, most famously with Marlene Dietrich in a tuxedo for the cabaret scene in Morocco (1930). The sissy and pansy character actors from the 1930s comedies, including Franklin Pangborn and Edward Everett Horton, receive their due as critics and flaunters of repressive gender norms. As the use of pansies declined, homosexual representation dropped, although homosexual males appeared as villains in several noir classics of the 1940s, including The Maltese Falcon (1941), Laura (1944), and Gilda (1946). Among the depictions carrying hints of homosexuality during the 1950s were the female juvenile delinquents in So Young, So Bad (1950), the scheming title character in All about Eve (19’51), the evil genius Dr. Terwilliker in the Dr. Seuss-scripted The 5,000 Fingers of Dr. T(1953), and the consumed Sebastian Venable in Tennessee Williams’s Suddenly Last Summer (1959).

The major earlier works about gays and lesbians on-screen, including Vito Russo’s The Celluloid Closet and Andrea Weiss’s Vampires and Violets: Lesbians in Film, were not as extensive a catalog of filmed depictions. Barrios does not address Weiss’s work and argues against Russo’s assertion that the images of sissy males and lonely, frustrated lesbians appeared in movies to promote the virtue of masculinity and the patriarchy. Barrios tends to view the amount of and approach to homosexual depictions in movies as dependent on the political climate of the era. Certainly, the Legion of Decency’s organization of boycott threats and establishment of a rating system led to a strengthening of the administration of the Motion Picture Producers and Distributors codes, which tamed the depiction of homosexuals in movies from their most licentious period in the early 1930s.

Similarly, the culture changed, and the companionate marriage system’s sexual mores, which defined proper love and romance as occurring between a husband and a wife, lost its dominance. When this occurred during the early 1960s moviemakers gained the ability to depict homosexuals as long as the work was serious. However, the book did not convince me of a direct relation? ship between approach to representation and the political attitude prevalent in the country. During the politically conservative 1950s The Big Combo featured a vice czar with two henchmen. The two, who were not labeled homosexual, appear as loving men sharing the same bed. In the more liberal 1990s a key character in Basic Instinct, while portrayed as lesbian (although not given the label), ends up being the ice pick-wielding killer. Many readers will find this book a valuable rereading of filmic homosexual images. Barrios uses the established methods of identifying homosexuals in these movies, including gender inversion, coded words, and cross-dressing.

Unlike Russo, who interpreted Franklin Pangborn’s sissy character in Only Yesterday (1933) as demonstrative of gay males’ mindless indolence, the author views the character as living in a milieu where he was accepted and had a boyfriend. The lesbians in the prison movie Caged (1950) are not simply ‘an equation of lesbianism with an outlaw social structure but appear as a refraction of Warner Brothers studio’s crime-and-punishment tales through a postwar toughness’ (216). However, the author’s inclusion of the gay sensibilities of Hollywood moviemakers, such as directors Mitchell Leisen and George Cukor, when their movies lack homosexual representation contributes little to the book. The author does not discuss one of the few times Cukor included a homosexual image, a cross-dressing woman dining at the Brown Derby in the movie What Price Hollywood? the precursor to A Star Is Born.

The book organizes the movies with homosexual images according to the decade of their appearance. In those times in which many movies contained homosexual figures, comic and dramatic depictions during the decade each receive their own chapters. Barrios groups the most frequently depicted homosexual figures into types that are commonly used in scholarship and understood by general readers, such as pansies and mannish women. He argues that at least during the early decades these images had some positive dimensions, such as being liked or fitting in within a milieu. These images as well as those from the 1940s to the late 1960s provided homosexuals in the audience with the opportunity to see someone similar to them and to know that they were not alone.

Scholars may be disappointed with the book’s limited discussion of the relationship of the filmic images to those homosexual images that appeared in other forms of popular culture during the era. Barrios does a solid job of comparing the images when plays have been made into movies. But there are opportunities to compare filmed images with depictions in other venues of popular culture. One might consider homosexual images from other plays and their similarities and differences with the images he found. Nor does he examine homosexual images from the literature of the era. Some of the types of figures Barrios found were examined in earlier scholarship. These include Richard Dyer on ‘sad young men’ in his book Matter of Images, Lillian Faderman regarding lesbians in pulp novels in the book Odd Girls and Twilight Lovers, and David Lugowski about ‘sissies’ in his article ‘Queering the (New) Deal.’

Scholars might want to examine whether certain types of inferences, coded phrases, or images depicting homosexuals appear in books or in movies or whether cross-fertilization occurred among the various media of a period. This book is a well-researched first step toward a broader examination of Hollywood product and Hollywood industry attitudes. The studios were more than an industry and producers of movies. Hollywood was a town and a cultural symbol. The studios created publicity photographs and endless articles about movie personalities and moviemaking. An entire entertainment reporting industry emerged to carry that publicity and generate more. Renowned and little-known novelists detailed the activities within the Hollywood studios and the industry’s influence on the culture in books.

The Hollywood novel is prevalent enough that scholars view it as a genre. Images and inferences of homosexuality appeared regularly within these materials, particularly during the decades prior to World War Two. Ronald Gregg detailed this in a piece about one star, William Haines, and I examined the use of gender and sexual nonconformist imagery to promote a wide range of women in Hollywood in a journal article last year. It would have been intriguing to know what relationships, if any, existed between the homosexual filmic images that Barrios catalogs and those that appeared in the Hollywood textual materials. Scholarship also argues that the movies promoted social conformity and served in the establishment of boundaries for culturally acceptable gender and sexual behaviors. This book misses the opportunity to comment on why this industry that promoted conformity would create these ‘more-positive’ images of homosexuals, as Barrios describes them. Brett Abrams Washington, D.C. Journal of the History of Sexuality, Vol. 14, No. 4 (Oct., 2005)

Check for it on:

Details

| ISBN | 9780415923293 |

| Genre | Film and Television |

| Copyright Date | 2003 |

| Publication Date | 16-Feb-05 |

| Publisher | Routledge |

| Format | Trade Paperback |

| No. of Pages | 416 |

| Language | English |

| Rating | NotRated |

| Paper Type | Electronic Format Available |

| BookID | 11173 |