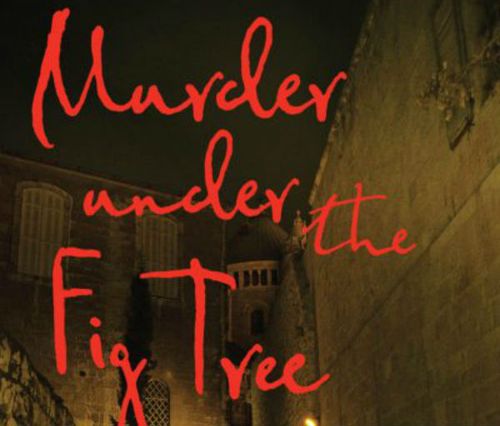

Murder Under the Fig Tree

Kate Jessica Raphael

Politics, tangled with personality, drove that book: This cop was compelled to solve crimes, and couldn’t ignore evidence even when ignoring it would be in her best personal interest.

Next on the list of smashed assumptions is the notion that a sequel to a murder mystery, involving the same investigators and some of the same auxiliary characters, will necessarily pursue a formula and soften the punch of the original. Murder Under the Fig Tree builds on the strengths of Murder Under the Bridge but quickly establishes itself as a uniquely powerful story, rich with surprises. Fig Tree opens with the Palestinian detective Rania, the officer who solved the murder in Bridge, in prison. Her loyal American Jewish friend, Chloe, who made herself a nuisance to the authorities in the first book and logged a few days of her own in an Israeli jail, returns to Palestine to help Rania–and reunites with her girlfriend, Tina.

What develops is more suspenseful, more complex, and sexier than the earlier book. The murdered woman in Bridge was a young trafficked Uzbekistani with no known loved ones. In Fig Tree, the victim is a young Palestinian drag queen who performs as “JLo Day-Glo” at a Jerusalem nightclub and is resigned to giving blowjobs to anonymous soldiers in exchange for passage through checkpoints so he can get to work on any given evening.

Rania is offered an opportunity to leave prison, on a deceptively simple-appearing condition: She must investigate the murder of JLo. The performer was popular with his Palestinian friends and Israeli fans, and beloved of the Israeli nightclub owner who was his boss. But he harbored dangerous personal secrets of the local occupying army force, and his flamboyant openness as a gay man brought his family deep shame. Rania will risk retribution from the Israeli military if she discovers that the young queen was killed by Army personnel. But she will suffer the suspicion of her Palestinian neighbors if she appears to be collaborating with the Israeli authorities and finds that he was slain by someone in his home community–or even by a member of his own family, in an “honor killing.”

We’re in Prime Suspect territory, with a single-minded detective who knows that whatever the outcome of her work, she will be pissing off people who have the power to hurt her.

Rania and her friend Chloe embody the proposition that well-behaved women don’t make history. The two are often antagonistic, even toward loved ones, but particularly toward men from whom they need information or cooperation. Their rash confrontations sometimes sabotage their short-term goals, and some would be hilarious if the stakes were not so high. Chloe, the American Jew, tries to help Rania with the investigation, thinking she is operating in the background. After hopelessly bungling an interview with a potentially helpful witness by accusing him of JLo’s murder, she laments–like the reader–that she has screwed up one more of many situations. At one moment while reading Fig Tree I found myself saying aloud, “If you can’t be nice to the guy, at least don’t provoke him!” How satisfying for a reader to find that fictional characters have become real enough to admonish.

The book’s generally serious tone does give way to a few welcome lighthearted moments. Raina wants to visit the nightclub where JLo performed, and persuades Chloe and Tina to accompany her there. As she witnesses the goings-on, with Israeli soldiers playfully giggling with young Palestinian men, she is both shocked and heartened. She gamely tries to believe that the heavily made-up dancers in heels, hoop earrings, and short skirts are men, and slowly absorbs an understanding that men can love men, and women can love women. As it dawns on her that Chloe and Tina may be more than “friends,” she becomes overwhelmed–so much to learn about the world!

Raphael maintains the book’s hyper-realistic tone in the bedroom, and much of the book’s sex is shaded with jealousy and anxiety. The grindingly familiar violence keeps us alert to the unfairness of life in an occupied territory. While still in prison, Rania passes the time in solitary confinement practicing Hebrew grammar–a skill that she begrudgingly accepts will advance her career if she is ever released. She resists her jailers in what she thinks are subtle ways, such as fashioning a makeshift flag for her cell from black, red, white, and green garments brought by her husband. In such small, mundane moments we learn much about her: “If you had told her a month ago that she could be so happy doing nothing but watching a Palestinian flag made of socks and underwear, she would have said you needed a psychiatrist.”

A gay Israeli soldier must hide his relationship with his Palestinian lover. A married Palestinian woman seeks out a lesbian support group–on behalf of a friend, but she will not let her husband know she is associating with such people. In its ingenious labyrinth, Fig Tree offers us bits of the facts as seen by various characters who cannot communicate with each other. Rania needs the help of the Israeli police to investigate the murder, but must not let them know that the victim was gay, because they could too easily write off his murder as an honor killing and halt the investigation.

Raphael has honed her gift for depicting the relentless unfairness of power politics. “Soldiers charged with murder,” Chloe reflects, on seeing a suspect handcuffed with his hands in front of him instead of behind his back, “were given a slight privilege over Palestinians charged with knowing too much.” In observations like this, Raphael reveals a definite political bent, and some pro-Israeli readers may not want to enter her camp. But she does not minimize the problems within the Palestinian community, and there is much for readers of every political orientation to learn. Rania herself “had no use for Hamas. She had joined the Fatah Youth Organization as soon as she was old enough to join anything. She found it painful to watch her people becoming more and more addicted to religion as the seeds of conservatism took root in the soil of isolation and oppression.” One of the driving conflicts of the novel involves the profound, possibly murderous homophobia in which the young Palestinian JLo lived in his village, and the irony of his popularity in an Israeli nightclub.

Most movingly, Raina watches her young son growing up in an ancient patriarchal culture, and longs to broaden his horizons. A male teacher tells him, in her presence:

“Your mother is a brave and intelligent woman. You are very lucky to have such a mother.”

“I know,” Khaled said. Rania beamed. She guessed there was nothing like the approbation of men to facilitate a son’s approval.

Like John le Carré, a writer with whom she shares many gifts, Kate Raphael masterfully sets up the interpersonal tensions that both reflect and sustain the geopolitical disturbance driving the story. Le Carré has famously perfected the art of “spy fiction” as a vehicle for historical exposition, political commentary, deep cultural revelation, and even romance, and sometimes includes a travel guide and language primer–all of it wrapped in a damn good story. Kate Raphael draws us deeply into the world of her characters’ daily experience, including the traditional family structures and gender roles, the recipes for labneh and manaqish, and even the teenagers’ T?shirts, emblazoned with the logos of U.S. sports teams, that make them uniquely who they are. I’ve learned more about the first and second intifadas from Kate Raphael’s writing than from many articles I have read on the subject, because she presents these events from the points of view of mothers, grandfathers, teachers, and children. Her characters reveal in personal terms the differences among the Hamas and Fatah parties, the Palestinian Authority, and other groups vying for legitimacy, whose names blur in U.S. news feeds. She enriches our understanding by using many Arabic phrases and quite a few Hebrew, translating dialect smoothly and naturally–employing a gift that many writers of international stories do not possess:

“Ahlan fiiki,” welcome to you too, Chloe replied “At lo rotzah ochel?” You don’t want food? Tali acted like she was going to put the tray back on the cart. Rania reached out for it, her hands through the bars.

A character familiar from Bridge is Benny Lazar, a blue-eyed senior Israeli police detective born in Minnesota. He encourages readers and other characters to expect humanity from him, but often seems to employ his ironically arched eyebrow merely to camouflage a bullying nature. “Benny liked Rania,” we read in Fig Tree, “and he had seemed to harbor no ill will toward Chloe, but that could all have been part of his act. He was capable of donning a lot of personalities.” Benny refuses even more adamantly than the other characters to behave predictably. This reader wonders what more he might reveal about himself in future volumes.

And future volumes appear to be a certainty. With this second novel–complex, informative, provocative, and entertaining–Kate Raphael is well on her way to establishing a significant reputation. ~ Steve Susoyev

Check for it on:

Details

| ISBN | 9781631522741 |

| Genre | Mystery |

| Publication Date | 2017 |

| Publisher | She Writes Press |

| Format | Paperback |

| No. of Pages | 320 |

| Notes | Lambda Literary Award Finalist, Mystery |

| Language | English |

| Rating | Good |

| BookID | 8566 |