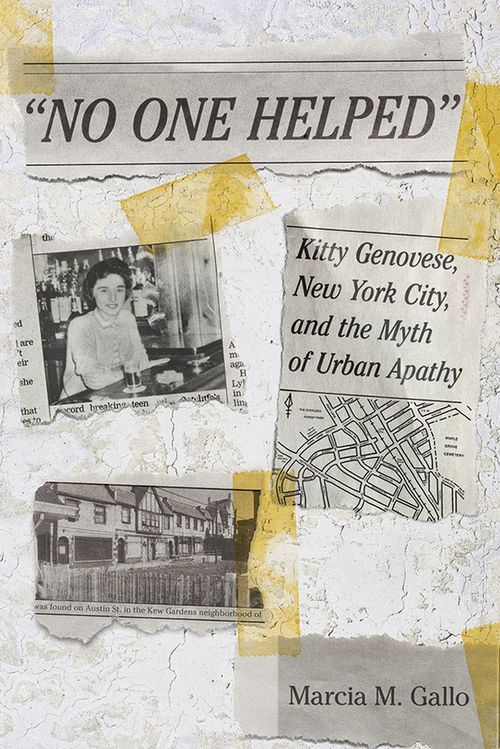

‘No One Helped’

Kitty Genovese, New York City, and the Myth of Urban Apathy

Marcia M. Gallo

This framing inspired the creation of a national 911 system as well as award-winning and field changing psychological research on ‘Bystander Syndrome’ that examined group dynamics and violence. Gallo charts these direct consequences of the crime, but the most intriguing and challenging aspects of ‘No One Helped ‘ comes when she goes a step further in her analysis of the ‘urban apathy’ myth. Gallo locates the power of ‘urban apathy’ in contemporary conversations over the developing crisis in Vietnam, the shifting racial demographics of United States cities, and the climaxing civil rights movement. She traces how the myth of urban apathy allowed Rosenthal to encourage intervention in Vietnam, to disapprove of post-war cities’ slowly growing racial and sexual tolerance, and to dismiss the activism of the civil rights movement as ‘impersonal social action’ that ‘infect[ed] the body politic’ (80).

Gallo then moves through time, demonstrating the new deployments of the Genovese legacy and attempts to rebuff ‘urban apathy’ that illuminated ‘the necessity for self- empowerment as well as community mobilizations to confront official indifference’ in the 1980s (133). Employing urban apathy as a larger political framework, Gallo connects a diverse, and often opposing, set of social and political movements from the decade that included feminist self-defense and anti-rape activism, the founding of ACT-UP and other AIDS activist groups, and the growing power of neoliberal discourse in both local and national politics. By the end of the century, Gallo assigns meaning to continuing social fascination and discourse around the Genovese case 40 and 50 years after the event as neighbors, friends, and family members challenge the lasting urban apathy narrative spun decades earlier. ‘No One Helped ,’ both ambitious and wide-spanning, is largely successful. Gallo ‘s clear, steady writing helps weave together the complex history she aspires to tell. But the sheer number of threads and the incredible detail she shares about each of them works against her at times. In tracing the full spectrum of issues and movements shaped, defined, or discounted by both Genovese ‘s legacy or the urban apathy myth, Gallo illuminates numerous areas for additional scholarship but also misses opportunities to enrich the work.

Gallo is clear to position race and civil rights struggles as a constant force in creating the Genovese legacy and the urban apathy myth, but a direct discussion of it at various points would have been powerful, as would a similarly frank analysis of emerging neoliberal politics. However, wanting more from Gallo reflects her skill and the many values of ‘No One Helped’ The myth of urban apathy as explored by Gallo proves a productive and rich mode of analysis sure to inspire future scholarship. By examining how and why the national fascination Kitty Genovese has endured for more than half a century, Gallo convincingly interconnects a bright young woman with the histories of sexuality, neoliberalism, racial justice and racism, feminism, psychology, and the post-war United States. ~ Katie Batza Source: American Studies, Vol. 55, No. 2, Summer Reading Issue (2016), pp. 97-98

Check for it on:

Details

| ISBN | 978-0801456640 |

| Genre | Non-Fiction; Black Interest |

| Publication Date | 09-Apr-15 |

| Publisher | Cornell University Press |

| Format | Paperback |

| No. of Pages | 240 |

| Notes | Lambda Literary Award Winner, Nonfiction |

| Language | English |

| Rating | Great |

| Subject | True Crime |

| BookID | 1 |