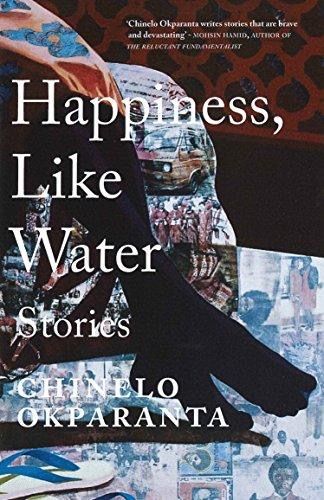

Happiness, Like Water

Chinelo Okparanta

The colossal invasion of colonial values, power, and greed is also felt throughout these tales of frustration and faint hope. Traditional aspirations of couplesthe passing on of the husband’s name through childrenare a prime cultural concern overriding personal interests and predilections. Mothers encourage their daughters to marry, and when married, to do what’s expected. In the happiest of circumstances, husbands are not aware a wife or child is unhappy.

This is the case in “Wahala!” Ezinne is barren, so she and her husband Chibuzo visit a dibia, a healer, on the outskirts of the Nigerian city Port Harcourt. Ezinne explains she feels pain when the couple has intercourse. Her pain is misunderstood, interpreted, misinterpreted. The dibia “nodded sparingly” and assures Ezinne that “ whether it was pain or just fear, she was sure she could cause it to disappear.” But of course the dibia cannot do what she has promised. “Wahala!” begins with charming foreboding. Chibuzo dreams he is seeing a vision on a bar of Ivory soap. Because it’s old and discolored soap, with cracks, he has trouble, even in the dream, understanding his vision. That image, of the husband not seeing what is before him, holds up at the end of the story, this time without the dissolving Ivory. Chibuzo isn’t cruel to Ezinne, but he doesn’t begin to acknowledge or understand his wife’s ongoing pain. A disturbing read.

In “Grace,” two women, one a professor of Levitican code and other “Old Testament” novelties, and her student Grace are drawn to each other. Unable to tell her mother she “doesn’t like men in the marrying way,” Grace is forced into an arranged marriage with a prosperous Igbo man. She reasons, or rationalizes, that “happiness is like water.” “We are always trying to grab onto it, but it is always slipping between our fingers.” The women share a moment and the narrator reflects, “the verge of joy is its own form of happiness.”

Most of the characters in these stories are Jehovah’s Witnesses, one of the evangelical, American transplants in Africa and a global anti-LGBT voice. (I don’t know just how important that is to Apocalypse-anticipating Jehovah’s Witnesses). Characters in Happiness Like Water derive some comfort from church, and also from older, native customs. I have empathy for Okparanta, who like her characters, was raised in a religious oddity-to-cult. I was raised in Christian Science. She (presumably) and her characters (appreciably) have the mitigating factor of friends, local culture, which includes older African beliefs, and also of education and travel. (I had the mitigating factors of the San Fernando Valley, three older sisters out of the fold, and a somewhat Jewish father.) But no factor fully makes up for the insanities and dangerous doctrines of a cult. Trust me. In Okparanta’s fictional world, the individual with quirks and original thinking only sometimes flourishes.

The family (Mama, Papa, and a daughter) in “Tumours and Butterflies” moved from Nigeria to Boston, for, as immigrants will, opportunity. Promised help with visas and green cards, Mama visits a church group in Florida, leaving Papa and the daughter to cope. So Papa cooks. The food, a constant throughout this collection, reveals the tortuous nature of his being, as the daughter narrates. “When Papa calls me to eat, there is a small tray of toasted bread, a stick of butter on a white saucer, and a plate of something in between scrambled eggs and an omelet, tomatoes and onion cubes scattered evenly; jagged and protruding, like raised scars across the top.” Mama returns, but without visas; the church group was a scam. Slowly and painfully for Mama as well as the reader, Papa is revealed as a batterer. Mama as trapped in a classic cycle of submissiveness and brutality. It’s a long cycle, not ending even when the daughter is an educated adult and Papa has terminal cancer. The daughter is collateral damage, but as observer, finally able to free herself as much as we can from our childhoods.

The food throughout keeps the stories rooted in a belief that we are sustained, even when the names are foreign. From “Runs Girl”: “It began with the pain in her shoulder. Mama decided that for dinner we should have some goat meat in pepper soup, with more than the normal amount of utazi leaves.” The narrator, a college student, and her classmate, the runs girl’ Njideka, are in the same government policy class. A runs girl is a gentleman’s escort, prositutute, sidekick on nefarious schemes a multitasker when it comes to surviving college alongside wealthy students in expensive shoes and with Bluetooth buds in their ears. A sick mother, mounting doctors’ bills, a friend who earns great sums of cash. Put it together. In this beautifully written story, however, not even a sickening compromise of morals serves the narrator’s family.

That sense that little can help or change life runs through the stories. Given the realities of life, it’s hard to argue a way out of that, but I admit to, personally, sometimes choosing the possibility or at least diversion of hope. Chinelo Okparanta is Visiting Associate Professor of English and Creative Writing at Purdue University. She has evocative writing talents, was doled charm, and expertly tragedies good fortune. I look forward to her next book. ~ Sarah Sarai

Check for it on:

Details

| ISBN | 9781847088314 |

| Genre | Fiction; Black Interest; Award Winner |

| Publication Date | 2013 |

| Publisher | Granta Books |

| Format | Paperback |

| No. of Pages | 208 |

| Notes | Lambda Literary Award Winner, Lesbian Fiction |

| Language | English |

| Rating | Great |

| BookID | 5139 |