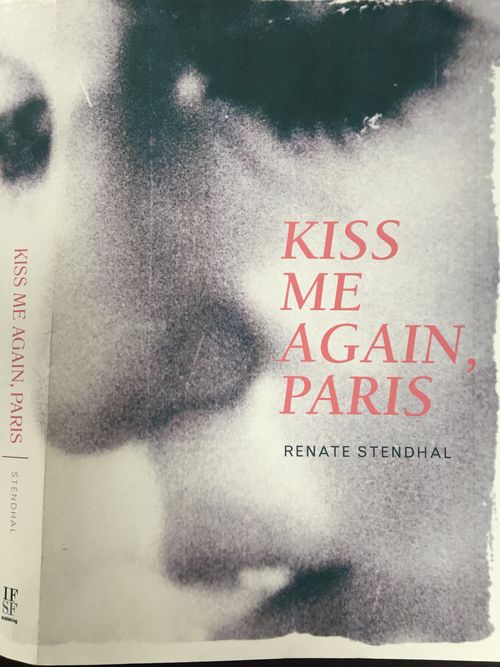

Kiss Me Again, Paris

or: How Many Drafts Does it Take to Change a Light Bulb?

Renate Stendhal

The Avatar game brought home to me how crucial it was, in writing my memoir, to conceive of two versions of myself, two personae. First, the secretly rebellious Lou (my father’s pet name for me, against my mother’s wishes) who is barely twenty when she runs off to Paris, leaving Germany, her stifling family, and an oppressive student husband behind. And second, the narrator-me, who observes from a certain distance (and with that skeptical smile) how this German girl arrived in Paris without a penny, had to make do with illegal jobs and little food, rely on lovers for a bathtub, and sneak into cultural events without a ticket. I used to be proud of the hardship. As a would-be writer, I believed in the bohemian myth of Paris–the romance of unheated attics, beautiful women and passionate affairs that is said to turn artists into Artists.

In Search of the Story

In my early drafts I was entirely caught up in Lou. I had no sense of any narrative distance: the memories simply galloped away with me. I named the memoir “My Thirteen Rooms in Paris,” and felt I had to tell about every room and everything in them. My gallop got bogged down, however, in details that one day seemed way too many. Was I really going to cover my whole youth and every episodic hardship and heartache? I was in my sixties when I started the memoir. If this was a “search for lost time,” did I plan to take to bed like Proust and spend the next decade in a cork-lined room, remembering every bit of the past?

My early readers told me I needed to focus. Yes, I wanted to write my story, but what was the story? Was there a story? I still had my old passion for Paris, even though every one around me was complaining that Paris wasn’t Paris any more. I disagreed. Paris was my main protagonist. Every time I went to visit, and especially when I went back to look at the sites and places linked to my past, I found most of them unchanged.

The “story,” I realized, had to focus on one particular moment in time that held in a nutshell what Paris had meant to me. A moment when the mythical promise that the City of Light could transform you forever, seemed real. This change, for me, had to do with sexual desire. At the end of the seventies, Paris saw the peak of an erotic wave that caught every woman who had been waking up and rebelling. Women were suddenly in fashion, felt empowered, inspired, reborn. Led by contemporary writers and thinkers like Monique Wittig and Christiane Rochefort, women’s liberation meant freely and openly loving women–as many women as possible. Role models were George Sand for cross-dressing, Gertrude Stein as a pioneer for lesbian living, Virginia Woolf for stating, “Women alone stir my imagination.” I was in my early thirties when I threw myself head over heels into this erotic madness that declared the end of couples, the end of gender-role divisions, and the beginning of complete sexual license.

With this “telescoped” perspective, what I had written in my previous drafts–my struggles to survive, doing ballet and underground theater before starting out as a cultural journalist–came to play the modest role of backstory. From “my thirteen rooms” I narrowed the scope to just one. From reminiscing about a whole decade, I chose one brief period when intellect and eros, politics and sex became inseparable.

Just chuck it

I was excited to show my new draft to my publishers in Germany, only to find that nobody shared my excitement. Apparently everybody was “dead tired of feminism.” Just chuck it, was the advice, nobody wants to hear about women’s issues any more. The same message came from an American agent. I had apparently been totally blind and outdated. This came as a shock and brought me to a halt for a couple of years.

When I recovered, I knew I had to take another step and question my desire to write this memoir. What was the point? Looking for insights and scouting around for books about wild youth movements from the sixties onward, I found only gay memoirs and stories (like Andrew Holleran’s Dancer from the Dance). For women, I discovered, this sexual awakening and radical rule-breaking in Paris was a story that had apparently not yet been told. The Parisian women’s scene, as I had experienced it, was a sexual avant-garde, and with hindsight, I saw it as a precursor of the polyamourous, gender-questioning, sex-positive movements of today. I decided to focus on this little known parallel and, in addition, convey some of the archetypal, timeless elements of a young woman’s coming of age in unexpected ways.

Fait accompli

In the next strategic overhaul of the manuscript, I treated women’s liberation as a fait accompli. No more need to explain. I simply reported what was happening in my life, in certain Parisian hot spots of sexual culture and experimentation–cafés, notorious nightclubs, artists’ studios and wild private parties. One could compare this technique with presenting a rosebush, showing off flowers in full bloom without showing the pruning shears, fertilizers and insecticides that had fostered this bloom. I felt oddly liberated by this move. I realized that I had in fact lived like that in the period I was talking about. I had taken sexual license for granted, the same as everyone else around me seemed to do.

Here’s youth for you, I used to think while writing my new draft: clueless and blind. Blind with desire. Here is Lou, my younger self, as she stumbles and falls into the traps of “freedom,” gets cocky, has more affairs than she can handle, walks around at night dressed as a boy, gets obsessed with the wrong woman, and stubbornly tries to avoid the risks of love. She doesn’t stop to wonder: what kind of fulfillment and happiness can there be without love? My older self, the writer-self, of course knew the answer, but I let Lou have her day, her proud day of freedom, with not too many questions asked.

What’s at stake?

So, I had back-storied my early Paris years, then strategically back-grounded a whole historical movement into an unnamed and yet all-pervasive presence with my rosebush trick. And I was done. By this time, I was at my fifth or sixth draft, unless it was already the tenth? I can’t say, but I can admit that with every single draft, I was convinced that this was it.

Running a few tests with professional connections (a good agent, a couple of American publishers) I was encouraged, but nothing conclusive came of it. Then a writer friend connected me with a freshly-minted independent publisher who was a lover of culture, Paris, and women. The contract I got was a dream come true that turned out to be the proverbial “too good to be true.” The company folded within a few months and I was back to square one. Well, not exactly.

I received a piece of editorial advice that made the whole painful disillusion worthwhile. The company’s editor said to me, “It takes a while before we find out where this is going. Why don’t you do what Sheryl Strayed does in Wild? She tells right away, in the first two pages, where she comes from, where she goes, and what’s at stake.” I pulled Wild out of my bookshelf and looked. It was indeed brilliantly done–done by the letter, as if the same editor had coached her. But I was reluctant. Did everyone have to do the same thing, follow the same rule? Wasn’t that a bit schematic, even conventional? “I like my beginning,” I said. “Sneaking into the Paris Opera without a ticket, falling in love with a stranger, and ending up with a tryst in a red velvet loge. I don’t really want to mess with it Couldn’t I explain all this in a foreword or introduction?” I wrote my foreword (talk about resistance), but not too surprisingly, the editor wasn’t convinced. Another prospective publisher came onto the scene and said, “I’d like to hear more about Germany–that need to escape.” He, too, seemed to be saying, where does she come from, and what’s at stake?

Now what?

Breaking through

The idea of a new concept, so late in the game, was overwhelming. I fretted and felt stuck again for a time, then did what I always end up doing with a critique or critical suggestion: I tell my ego to shut up and listen closely to the message for what might be of value in it. Then I embrace it.

“Where does she come from, where is she going, and what’s at stake?” changed the memoir. The darker shadings and contradictions in my own character now began to interest me. I wasn’t just driven by the post-War oppression of Germany, a country that had to silence and whitewash its crimes with puritanical vigor. My sexual compulsion and acting out seemed to be driven by fear as much as by desire: a fear of losing my hard-won freedom by getting trapped in another relationship of silence and lies. Lou, my young self, did not believe in romance. Why was she convinced that love was not meant for her and could never be?

I had not raised this question in any of my drafts. But I realized that it had come with me the day I arrived in Paris. What was the intimate root of this avoidance, hidden in my past, in Germany? What was the secret I’d been hiding from myself?

I felt pulled forward with a new urgency. Writing about a mystery that had to be solved, I quite naturally moved toward a more fictionalizing narrative. I had already taken pains in my previous drafts to set up “scenes” around my memories, capture moods and weathers, conversations and events with the attention of a novelist. Paris had been a major presence in all my drafts. Now I worked on bringing out the dramatic arc of my story, compressing timelines and taking leaps in order to work up suspense, as if I were writing a “mystery story.” Author Rachel Cusk, in her memoir Aftermath, says that when people want to know about her life, she asks if they want the story or the truth. “The story has to obey the truth,” she writes, “to represent it like clothes represent the body. The closer the cut, the more pleasing the effect. Unclothed, truth can be vulnerable, ungainly, shocking. Over-dressed it becomes a lie.”

Kiss Me Again, Paris

I felt more truthful about my younger self in this writing that went closer to the bone and adhered less slavishly to chronology and factual details. Lou felt much more like me, now that I questioned her cockiness and brought to light her doubts, her self-inflicted torments, and secret longings buried in the past, in Germany. I discovered a more tender acceptance of my younger self, but also a new worry: Did this “closer cut” get too close? Getting close always holds a risk, in sex as well as in writing. I tried to make sure to keep enough “clothes” on to cover myself (and protect the privacy of certain lovers and friends) –and preserve enough of the glory of youth, the golden fairy dust of a “lost time.” The undeniable nostalgia of looking back gave me the new title for the memoir, Kiss Me Again, Paris.

At the same time, I noticed that the vantage point of maturity (make that, getting older) snuck in a sense of humor that I didn’t have as a young woman, caught up in the drama of passion. Humor, playful irony come with hindsight. Clearly, turning more personal and confessional had not eliminated all narrative distance. A curious amalgam of my younger and older self seemed to have taken the memoir in hand.

This now was a final draft. (Wasn’t it?) ~ Renate Stendhal

Check for it on:

Details

| ISBN | 978-0-9859773-8-2 |

| Genre | Autobiography/Biography |

| Publication Date | 2017 |

| Publisher | IFSF Publishing |

| Format | Softcover |

| Notes | Lambda Literary Award Finalist, Lesbian Memoir/Biography |

| Language | English |

| Rating | Good |

| BookID | 6401 |