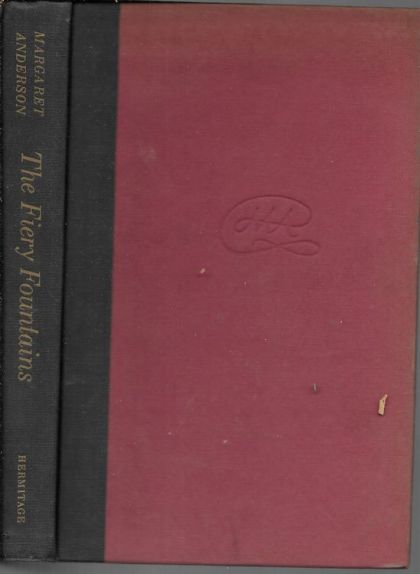

The Fiery Fountains

Continuation and Crisis to 1950

Margaret C. Anderson

Now after a generation spent largely in Europe she has continued her autobiography in The Fiery Fountains, a book which will have less general appeal than the earlier volume because of its more restricted personal preoccupations. She takes up her story in 1924, when she settled in France with her friends, Jane Heap and Georgette Leblanc; the one was a mainstay on the Review, the other an actress and singer who had been the wife of Maurice Maeterlinck. They had powerful connections but little money, and as they moved about France living alternately in an abandoned lighthouse and the wing of a chateau, their existence derived stability and fulness (sic) from conversation on art and life, for conversation was often almost literally their meat and drink.

Miss Anderson conceives this period between wars in terms of body, mind, and spirit; she therefore writes of ‘a life within a life,’ giving an account of external events, followed by a study of her personality and temperament, and, delving deepest, presents an intense but virtually incommunicable impression of the mystical studies in which she engaged. Miss Anderson is primarily a ‘personality,’ whose rebellion against her conventionally-minded upper middle class parents provided her basic physical and emotional drive. Through sheer energy and persuasiveness she ran the Little Review, but its distinction came from her powers as a catalytic agent and from her ‘instinctive’ approach to editorship. Those very capabilities guaranteed a vibrant and exciting life for the three women who dominate this book, and that quality of intensity is successfully communicated.

Essentially, however, she strives to recount a story of the inner life, an ambitious task which calls for mature intellectual and philosophical gifts which she does not possess. She became attracted by the age-old riddle of the meaning of life and by the possibility that modern science may have given us new ways of solving the problem. She came under the influence of G. I. Gurdjieff, a ‘scientific’ mystic whose system of esoteric knowledge combined Western and Oriental elements of philosophy, psychology, and science, and whose personality was sufficiently magnetic to create yet another cult. She does not succeed in disarming the natural suspicions of the general reader, nor does she provide an intelligible exposition of the ‘law of three and the law of seven’ said to govern the universe. (That job has since been tackled in Kenneth Walker’s Venture with Ideas , a book that profits from its author’s background as a British surgeon.)

We do understand that Gurdjieff directed her groping and that by 1938 she had come to understand a few key phrases never vouchsafed the reader which changed her relationship to the world. But one struggles in vain to understand precisely the nature of the new insight. When she tries to summarize the result of her experience she uses language which, like the experience itself, defies analysis: I saw myself no longer sitting on a cloud; nor was I left sitting on the ground. I was no longer unhappy, nor would I be happy again. I would never be anything but rejoicing. A blessing was upon me, I felt it on every side. I would no longer be spared, or killed, or protected. I would be helped. If this section of her book disappoints, it is not that we doubt that man must be born again or that mystical revelations can be real.

It is rather that her pages retain so much of the personalism of a diary that they communicate only the atmosphere of an experience, without its substance. The final section of the volume is humanized by Miss Anderson’s account of the war years in France. The details of life under German occupation are bizarre and often touching. But the focus here is chiefly on Mme Leblanc. Her personal heroism in the face of an incurable illness is the story of an unconquerable spirit whose philosophical serenity seems to exemplify the very relationship of man and universe that Miss Anderson was seeking to achieve. ~ Claude Simpson, Southwest Review, Vol. 37, No. 2 (SPRING 1952)

Check for it on:

Details

| Genre | Autobiography/Biography |

| Publication Date | 1951 |

| Publisher | Hermitage House |

| No. of Pages | 242 |

| LoC Classification | PN4874.A5 .A26 |

| Language | English |

| Rating | Good |

| BookID | 3943 |