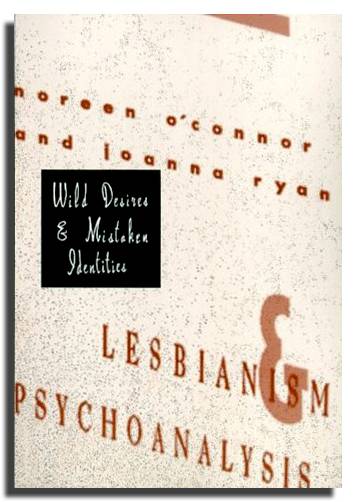

Wild Desires and Mistaken Identities

Lesbianism and Psychoanalysis

Noreen O’Connor; Joanna Ryan

The book’s objective is to ‘initiate a dialogue about psychoanalytic theories of female homosexuality’ (p. 12) that challenges the still dominant, pathologizing view of lesbianism as either a perversion or an ill- ness. The authors want to open up a ‘theoretical space in psychoanalytic theory’ (p. 10) where conceptions of homosexuality may be recast in light of the developments that have occurred since Freud, up to and including feminism. To this end they examine an impressive number of theoretical writings and case histories, some well-known and some less so, representative of a wide range of positions, from Sigmund Freud, Helene Deutsch, Karen Horney, Ernest Jones, and Joan Riviere to Melanie Klein, Masud Khan, Charles Socarides, Donald Meltzer, and Robert Stoller.

There is a chapter on Joyce McDougall; one on Jacques Lacan, Julia Kristeva, and Luce Irigaray; feminist works from Juliet Mitchell to Nancy Chodorow and from Jessica Benjamin to Diane Hamer; and much more. The authors are psychoanalytic therapists in private practice in England, trained at the London Philadelphia Association. Joanna Ryan holds a Ph.D. in psychology, and Noreen O’Connor in contemporary European philosophy. Their project of rethinking lesbian sexuality within and against the orthodox paradigm proceeds from their institutional location in clinical practice and has the therapeutic goal of helping lesbian patients ‘create and sustain erotic partnerships’ (p. 252) in the face of social oppression. Thus, perhaps necessarily, their book has two goals or drives: one critical, deconstructive (Foucault and Derrida are mentioned in the first pages of the introduction), the other therapeutic, reconstructive.

These goals do not set up an opposition between theory and practice. On the contrary, the book consistently underlines the mutual imbrication of theory, as a modality of reading, with the textual material being read, the material of clinical analysis. Nevertheless theory- or rather, which theory-remains a thorny question throughout the book. O’Connor and Ryan are opposed to the developmental or etiological theory of homosexuality espoused by most contemporary psychoanalysts in the Freudian and Kleinian traditions. They also reject the notion of psychic structures like the Oedipus and the imposition of such interpretive schemata on the patient’s words. Instead, they insist on the ‘irreducible uniqueness’ (p. 266) of each patient and each analytic relationship, with a strong emphasis on the function of countertransference, and argue for an approach that is more descriptive than interpretive.

By this approach, which they name post-phenomenological, they attempt to combine the critical/deconstructive project with the therapeutic/reconstructive one, and presumably reconcile the epistemologically divergent drives of poststructuralist, antihumanist philosophy and a phenomenology that remains fundamentally humanist. ‘Whilst we use aspects of existing psychoanalytic theories where we feel these are productive and illuminating, we do this in the spirit that they provide phenomenological descriptions both of the patient’s experience in the world and of the interaction between therapist and patient, always open to revision, rather than imposing a rigid schema on the patient’s communications, or claiming to know the truth about the patient’ (p. 17; emphasis added).

This may make good sense in clinical practice, but it raises a more general theoretical question the authors do not seem willing to con- front. If the verbal representation of the patient’s experience is read through ‘aspects’ of various theories that the therapist finds illuminating and productive for the analytic interaction, then there may not be the imposition of a rigid schema on the psychic text of the patient, but there is nonetheless the imposition of some schema, some conceptual/ discursive frames, through which memories and feelings get translated into the language of ‘phenomenological description.’ In other words, the question of interpretation, implicit in description, returns us to the question, ‘Which theories are ‘productive and illuminating,’ and why? A result of O’Connor and Ryan’s methodologically inductive and theoretically ‘pluralist’ approach is the sliding of certain terms from one discursive register to another. For example, the term sexuality slides into and becomes interchangeable with sexual identity (which is more socio- logical or psychological as a category than psychoanalytic); similarly, lesbian desire is described in relation to sociopolitical oppression (p. 273), where one might have expected repression or another intrapsychic mechanism.

Thus, on the one hand, they usefully stress the constructedness and contingency of lesbianism. On the other, however, the only thing they see lesbians as having in common is ‘lesbian oppression, or the social construction of lesbianism’ (p. 272). Certainly, to define lesbianism either in political terms, as an effect of social oppression, or in individualistic terms, as contingent on the ‘irreducible uniqueness’ of each personal relationship, has strategic and corrective value vis-a-vis clinical and more broadly social practices that are conservative, pathologizing, and indeed oppressive. But it does not advance the psychoanalytic theory of sexuality. Such a generalization as ‘lesbian oppression,’ no less than the relativism entailed by focusing on the singularity of experience, leaves unanswered the question, What is lesbian sexuality? How does it come to pass that some women-not all, not just one-desire another woman?

Much as I concur with O’Connor and Ryan’s incisive critique of dominant theories of homosexuality, and much as I share their sense of how very hard it is to ask the question of lesbian desire in psychoanalytic terms without implying psychopathology and without recourse to etiological or developmental theories, I nonetheless believe that question must be asked. Their book is an immensely valuable guide to all fellow travelers, including those willing to venture on the road they have not taken, for it provides both a detailed map of the discursive terrain and the recognition of the urgency of the question. ~ Teresa De Lauretis, History of Consciousness, University of California, Santa Cruz. As appeared in Journal of the History of Sexuality, Vol. 6, No. 4 (Apr., 1996).

Check for it on:

Details

| ISBN | 9780231100229 |

| Genre | LGBT Studies/Social Sciences |

| Copyright Date | 1993 |

| Publication Date | 1993 |

| Publisher | Columbia University Press |

| Format | Hardcover |

| No. of Pages | 315 |

| Language | English |

| Rating | NotRated |

| Subject | Lesbianism – Psychological Aspects; Lesbians – Psychology; Psychoanalysis And Homosexuality |

| BookID | 14612 |